The Tree of Life: 3.3. Swami Krishnananda.

=====================================================================================

Tuesday 08, July 2025, 19:40.

Shrimad Bhagavad Gita

The Tree of Life: 3.3.

Discourse: 3. Severing the Root of this Tree of Life:3

Swami Krishnananda.

=====================================================================================

Note:

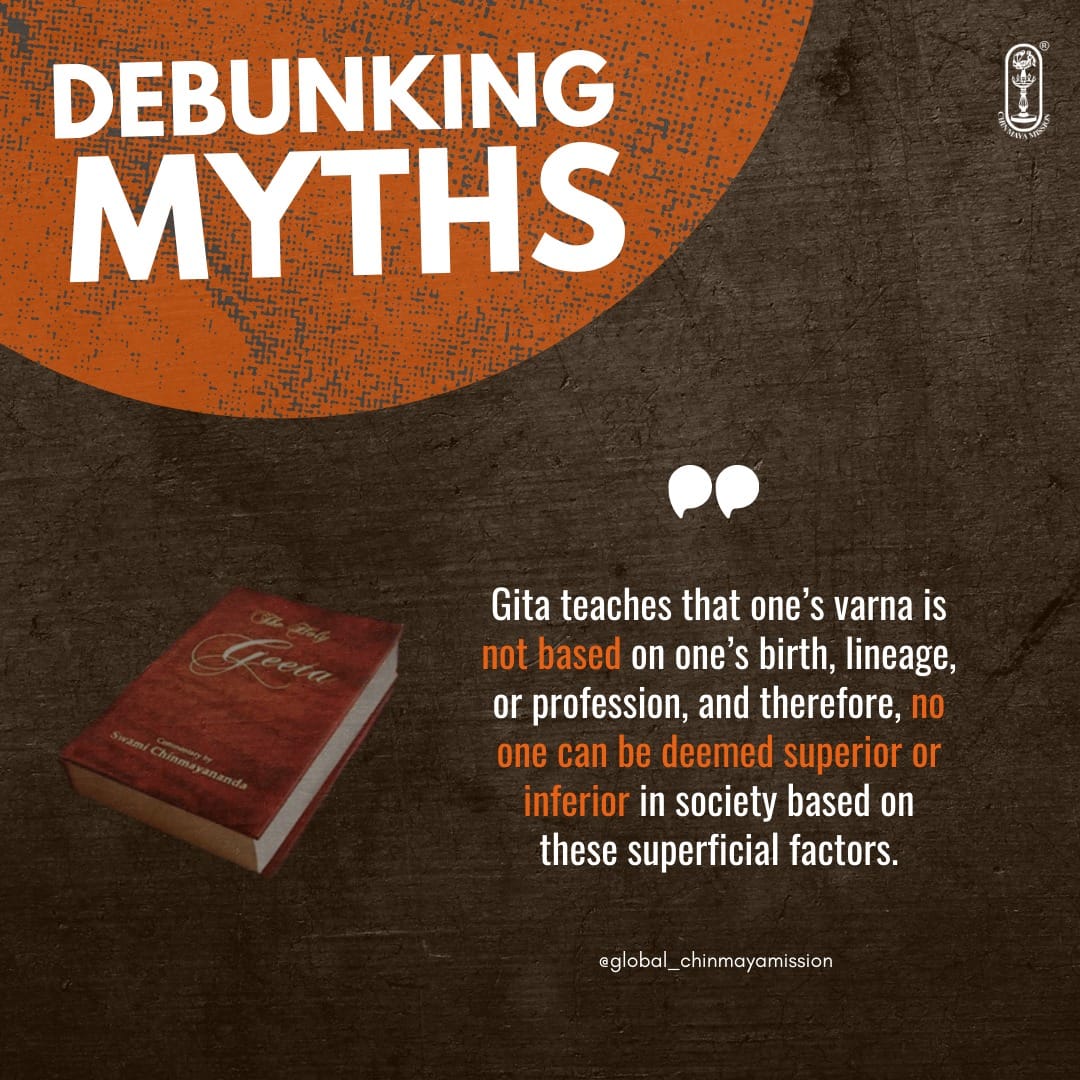

"The Bhagavad Gita discusses the concept of Varnashrama, not as a rigid caste system based on birth, but as a system of social organization based on individual qualities and duties. Krishna explains that the four varnas (Brahmana, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra) are created based on "guna" (qualities) and "karma" (actions). While the Gita acknowledges the existence of these divisions, it emphasizes that one can attain liberation (Moksha) through fulfilling one's prescribed duties (Swadharma) within their respective varna, regardless of their birth"

"chatur-varnyam maya srishtam guna-karma-vibhagashah

tasya kartaram api mam viddhyakartaram avyayam."

BG 4.13: The four categories of occupations were created by Me according to people’s qualities and activities. Although I am the Creator of this system, know Me to be the Non-doer and Eternal.

==========================================================================================

In certain scriptures we are told that knowledge of this tree is the knowledge of the Absolute, so that it is identified with some aspect of Ultimate Reality itself. But the Bhagavadgita wants us to cut at the root of this tree with the axe of non-attachment. The Gita is oftentimes known as anasakti yoga, the yoga of detachment or non-attachment, and the whole of yoga is only this much, at least from one point of view. It is an art of detachment. But it is not merely a negative process of withdrawal of something from something else. That is why we have both sides of the picture presented before us. On one side, it is the act of severing the root of this tree; on the other side, it is knowing what this tree is.

This double feature of the tree consists in the fact that the root of this tree is in the Eternal but its branches are spread out in the phenomenal realm. It is just like the human being whose personality stretches from Earth to heaven through all the levels of experience through the various realms or lokas. Everything is in every level at all times, but we are conscious only of one level at any given moment. Though even just now our personality is stretched from the nether regions up to the highest heaven and we can operate upon any level at any time, our egoism tethers us to a particular type of experience. At present, in our case, it is physical experience, which keeps us completely oblivious of even the presence of other levels of our own personality. In a more crude form, psychoanalysts tell us that we have layers of psyche within us of which we are unconscious, and we are presently operating in the so-called conscious level of the mind, not knowing the deeper level is buried in the abysmal depths.

More true is the case with the vaster implications of the human personality. We really exist everywhere in all levels, vertically as well as horizontally. But this is something strange to hear for the mind that is accustomed to think in terms of finite objects which are placed only in one place, located in space and time, and are cut off from our own personalities as bodies. So when it is told that by the shastra of asanga the root of this tree has to be severed, that monition is towards the necessity of withdrawing the consciousness from involvement in objectivity of experience. Here again we have a tremendous problem before us. We have heard about this detachment so many times that this term has become commonplace. Everyone knows what this detachment means, but no one has fully succeeded in the practice of this type of detachment that is required by the Bhagavadgita.

When we think of detachment, we generally conceive of physically moving out of our house, going a few thousand miles away, and then it is detachment. This is the crudest form of the notion of non-attachment in the field of spiritual life. But our bondage does not consist in our physical location in any place. It is not the house that binds us. It is not the land on which we are seated that is our problem. Nothing visible to the eyes as a physical content can be regarded as a bondage. The bondage is a kind of experience that is injected into our consciousness. Our happiness and sorrow are a type of consciousness, a feeling, an operation of the psyche in some way, and if the mind is to work in a different way, we will have a different kind of experience. So we are concerned with experience rather than with objects.

Therefore, if the experience does not change even after isolation of the body from its physical atmosphere, that would not be counted as detachment, or non-attachment. What the mind is thinking is the touchstone of success in the practice of non-attachment. You may be having a house in Switzerland but you are physically seated in the Himalayas. Will you call this detachment? You may say, “Yes, why not, because my house is in Switzerland and I am not there. I am here.” But what is the mind thinking? Is the mind conscious that it has a property? That would be a subtle silken thread connecting the consciousness with its object, which can slowly become stronger, strengthening itself into an obstacle in the direction of the mind towards the spiritual goal of life.

Comments

Post a Comment