The Bhagavad Gita – A Synthesis of Thought and Action: 4. Swami Krishnananda

Chinmaya Mission:

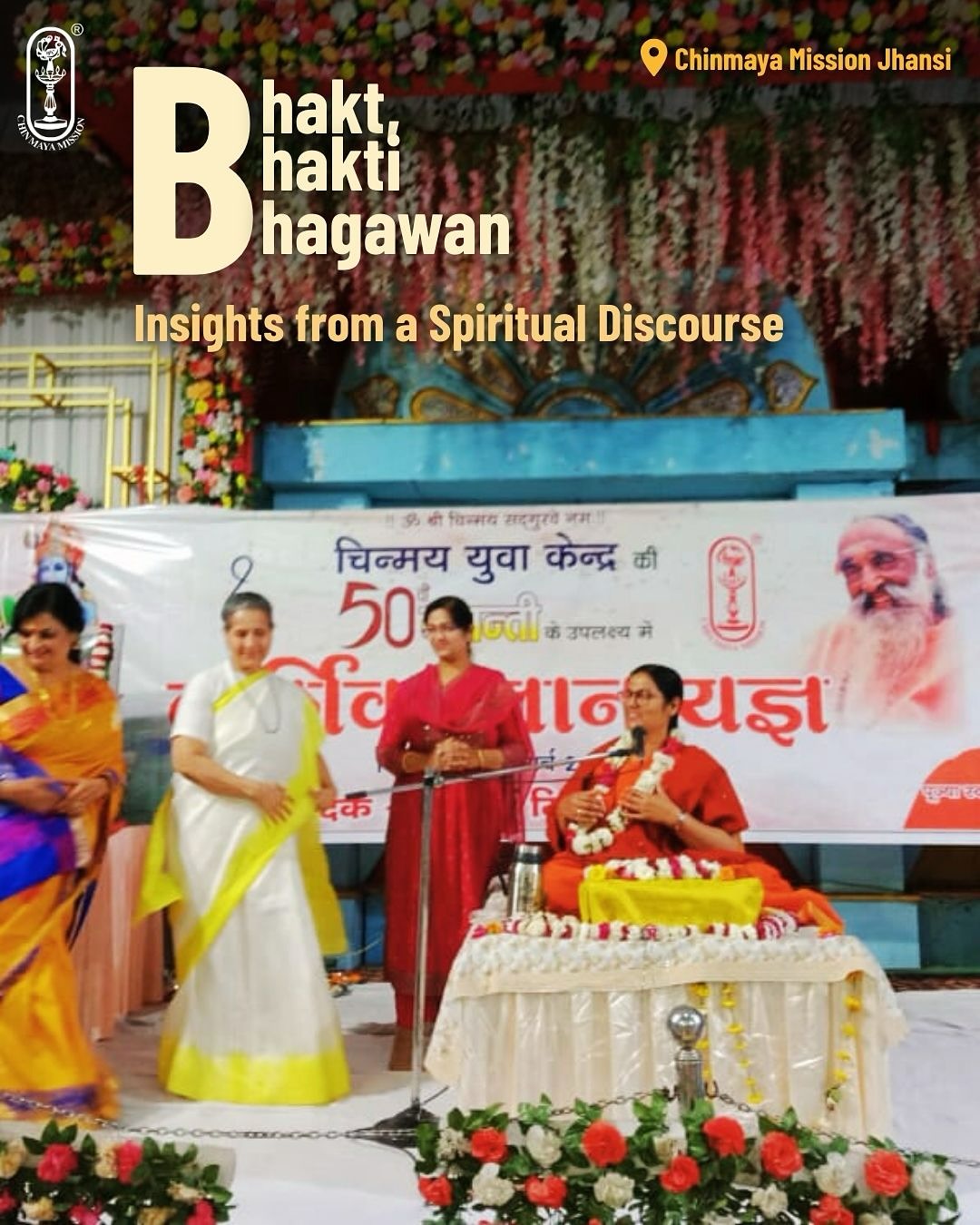

Under the auspices of Chinmaya Mission Jhansi, a spiritually enriching Jnana Yajna was organized.

The event was graced by the revered Swamini Sanyuktanandaji of Chinmaya Mission Bokaro, who captivated the audience with her clear and thought-provoking discourses. The morning sessions explored the essence of “Dhanyaashtakam,” while the evening sessions delved into the 12th chapter of the Shrimad Bhagavad Gita, reflecting on the profound theme of “Bhakt, Bhakti aur Bhagawan.”

The Yagya was further supported by Br. Raghavendra Chaitanya and the dedicated members of the Chinmaya Executive Committee. Respected guests Sh. Hari Om Pathak and Smt. Anuradha Sharma also graced the occasion with their presence.

More than 300 devotees from the city actively participated in the sessions, making the event a truly inspiring and elevating experience for all involved.

=======================================================================================

Tuesday 15, April 2025, 10:45.

Article

Scriptures

The Bhagavadgita:

A Synthesis of Thought and Action: 4.

Swami Krishnananda

(Spoken on Gita Jayanti in 1973)

=========================================================================================

The rightness or the wrongness of an action does not depend upon the pleasure or the pain of the individual concerned in the action; this is the first warning given to us in the Bhagavadgita. We are likely to think that what brings us satisfaction is right and what brings us sorrow or grief, unhappiness, is wrong. This is an unfortunate, hedonistic approach which cannot be ultimately justifiable from the scientific point of view. A scientific principle does not care for our pleasure or pain. When we talk of a scientific principle, we speak of a truth that holds good for every person under all circumstances, irrespective of the emotional condition of the individuals concerned. So our joy or sorrow, personally and individually speaking, cannot become the standard of reference for the rectitude or otherwise of an action.

Arjuna thought that it was a horror before him in the form of a war presented before his terrified eyes. He was not happy. “Krishna, I am very sorry. I think what I am going to do is wrong.” He thought that the action upon which he was about to embark was going to be wrong, inasmuch as it shook his emotions and tore his personality. He was intensely grief-stricken. So you intend to judge actions from the point of view of your personal happiness – if you are happy, it is all right; otherwise, it is not all right. This is not the correct approach, says the Bhagavadgita.

Now, again we go back to the Upanishads. Why should the rectitude or the otherwise of an action not depend upon the pleasure of the individual or the otherwise? The Upanishads give an answer to it. The nature of existence itself is contrary to holding such an opinion. The structure of all phenomena is of such a character that it will not permit us to hold such an individualistic opinion in respect of any action whatsoever. The universe does not belong to you or to me particularly. It does not belong to anyone. As such, we can say that nothing in this world belongs to us because everything belongs to the universe. It is a part of the world. And as the world is the basic repository of even our own personal existence – we belong to the world rather than the world belongs to us – nothing can belong to us. If nothing can really belong to us in the proper judgment of values, on an impartial judgment of things, how can anything give us pleasure or pain? The pleasure or the pain that we seem to be receiving from the context of particular objects or groups of objects outside – this pain or pleasure which is a reaction to the stimulus from objects outside – arises on account of our possessiveness or the establishment of a specific relationship in respect of the objects of the world, which is unjustifiable, scientifically speaking. We are not permitted to establish particular relationships with anything in the world, as nature is a wholly unselfish entity bearing no positive or negative attitude towards any content thereof.

If the world is a single unity, of which we are also an integral part, accepted, no object or person in the world relates to us in any personalistic fashion and, therefore, no one in the world can bring us happiness or sorrow. Our individualised happiness or grief is an immediate outcome of our so-called relationship with certain persons and things in the world which ultimately does not exist, and cannot be justified.

The Upanishads speak of the ultimate truth of things. Yo vai bhūmā tat sukham: The Plenum is felicity. And what is the Plenum? What is this Bhuma which is the source of real bliss? The Chhandogya Upanishad tells us: yo vai bhūmā tat sukham, nālpe sukham asti (Chhandogya Upanishad VII.23.1); yatra nānyat paśyati nānyac chṛṇoti nānyad vijānati sa bhūmā (VII.24.1). Where you are not permitted to look on any object as an external something, that is the Supreme Plenum. But where you are drawn down to the level of an individualistic perception of such and such a thing being personally related to you, that is finitude of consciousness. It is not the true nature of things. Satyam eva jayate nānṛtam, satyena panthā vitato deva-yānaḥ, yenākramanty ṛṣayo hy āpta-kāmā yatra tat satyasya paramaṁ nidhānam (Mundaka Upanisahd 3.1.6), says the Upanishad. Truth succeeds; untruth will never succeed. And what is the truth? The Plenum is the truth. And what is the Plenum? Wherein you are not to look upon anything as an isolated something or a disjointed object separated from your own existence, that is the Plenum.

*****

Continued

Comments

Post a Comment